In my first installment of this series, I explained how the incredibly important size principle works. It’s crucial to understand that information, so if you haven’t checked it out you can do so by clicking here.

In my first installment of this series, I explained how the incredibly important size principle works. It’s crucial to understand that information, so if you haven’t checked it out you can do so by clicking here.

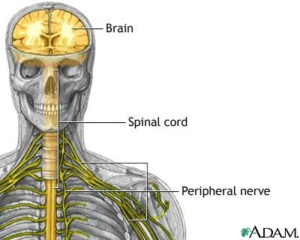

To recap, all movements start in your brain, and then travel down your spinal cord where the signal stimulates the motor neuron to contract your muscles.

Now, I’m going to take things a step further by explaining the essential component of any training program that’s designed to build muscle, boost strength, or burn body fat.

What is the essential principle that I live by? You must recruit as many motor units as possible with every rep of every exercise. The only way to do this is by following training parameters that tap into your largest motor units.

Here’s why that’s important. You see, according to Henneman’s size principle, if you’re tapping into the largest motor units you’re also recruiting all of the other motor units (from smallest on up).

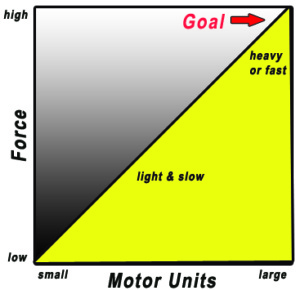

Check out the graph on the right that shows the relationship between force and motor unit recruitment. The highest levels of force coincide with the highest level of motor unit recruitment. There’s no reason to ever do a rep, set, or workout that doesn’t target as many motor units (muscle fibers) as possible, therefore, keep this graph in the back of your mind.

Ok, at this point a logical question surely popped into your mind: “How do I recruit all my motor units?”

There are two ways: lift as heavy as possible, and lift as fast as possible. Now, keep in mind that heavy weights won’t move quickly, no matter how hard you try. But they don’t need to. When the weight is heavy enough to only allow three or four reps, you’re recruiting all your motor units because it takes every ounce of effort to get the weight moving.

Where many people screw up, however, is with submaximal weights. I’m talking about lighter weights that you could move faster, but don’t. If you start with a weight you could lift 12 times, and if you lift with a slow tempo, you’re probably recruiting about 60% of your motor units. But if you accelerate the lift from the first rep as fast as possible – wham-o! – you’ve tapped into all the motor units that were sitting on the bench.

So there are two ways to recruit all your motor units: lift heavy weights some of the time, and lift lighter weights as fast as possible other times.

There’s another essential aspect that I want to mention with regard to lighter weights. It’s not the load of the weight that’s important – it’s the effort and intensity that will make or break your results. With enough focus and drive you could theoretically recruit more motor units with 50% of your one-repetition maximum compared to, say, 75% of your one-repetition maximum.

Now, here’s a critical component of the equation that many people don’t think about: “How long can I sustain maximum motor unit recruitment?” This, my friends, is the key to getting this powerful training concept right.

Remember I said that the goal of any rep, set, or workout should be to tap into your largest motor units (aka, largest muscle fibers)? Well, your biggest, strongest muscle fibers can’t maintain their activity for long since they rely on the short-acting ATP-PC energy system. This is a readily available supply of energy in your muscles that allows you to immediately tap into the “fight or flight” response. However, since it’s a small pool of energy, it can only maintain your maximum efforts for 10 seconds.

In other words, you only have 10 seconds of available time to recruit all your motor units. This is why so many lifters immediately got results when I told them to switch from 3 sets of 10 reps to 10 sets of 3 reps. With 3 reps, you’re finishing each set in less than 10 seconds. In either case you’re performing 30 total reps, but with 3 reps instead of 10 reps per set, you’re able to take advantage of maximum motor unit recruitment with every set.

Now, keep in mind that the “10 seconds maximum” I mentioned can differ from person to person. Some lifters will only be able to sustain maximum motor unit recruitment for 6 seconds, whereas others can pull it off for 12 seconds. That’s why it’s important to know which cues tell you that motor units are dropping out of the task. It’s important to keep in mind that the largest motor units are recruited last, but drop out first. So you must first tap into them as quickly as possible by lifting heavy or lifting lighter weights fast. Then, you must know when those largest motor units are dropping out.

How do you know? There are three cues. First, your speed will slow down dramatically. Second, your range of motion will shorten. Third, your technique will break down. These don’t all happen in the order I mentioned. For some exercises, such as the pull-up, your range of motion will typically shorten before your speed slows down. For technical lifts such as a hang snatch, your technique will falter before your speed decreases. However, for most common strength exercises your speed will dramatically slow down when motor units start dropping out.

“The last few reps of a set is where the results happen,” has long been the dogma in resistance training circles. The theoretical reason why some coaches said this was true is because they figured that additional motor units were recruited at the end of a long, agonizing set to failure. However, if you look at the neuroscience research it’s clear that this postulate holds no water.

If you recruited more motor units in the last few reps to failure, the set would get easier and the speed would increase. Since this doesn’t happen it’s time to look at a more progressive way of training. Lift heavy, lift fast, keep the sets shorts, and avoid failure. Those are the keys to maximum motor unit recruitment.

In my next installment I’ll discuss some exciting new research that uncovers new ways to tap into your largest motor units.

Stay focused,

CW