I’ll bet you’ve read an article that quoted intriguing research. Maybe that research was exactly what you wanted to hear: “Group X lost 320% more belly fat than those that didn’t take the pill!”

I’ll bet you’ve read an article that quoted intriguing research. Maybe that research was exactly what you wanted to hear: “Group X lost 320% more belly fat than those that didn’t take the pill!”

Sure, you assumed it was too good to be true. But it was a published study, so that must count for something legit, right?

Learning how to identify whether a study is reputable or garbage is an essential part of the information-building process. If you assume any study that’s published is credible, you’ll surely be suckered into believing a product, exercise or workout is reputable when it’s really not.

Today I’m going to cover 8 different categories of research. So the next time you read a story or article where the author bases his position – or sales pitch – on published research, you’ll know whether or not it’s legit.

I’ll start from the least credible category of research – the dreaded and overly-quoted animal studies – and work my way up the pyramid until we achieve research awesomeness.

Ranking Research From the Bottom Up

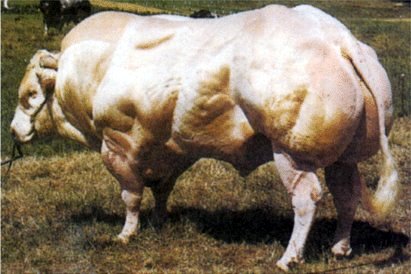

Foundational basic science: these studies are performed with animals or cadavers and rank at the bottom of the credibility pyramid. Don’t get me wrong: animal studies aren’t useless because it’s where virtually all medical research starts. But let’s be real, when it comes to building muscle we all know those animal results rarely carry over to human physiology (see the myostatin bull below).

Narrative reviews, expert opinions, textbooks: the next step up in credibility is an expert’s opinion or textbook. On the surface, this type of research appears pretty solid – and it certainly can be – but the author’s bias and no “results section” to explain can heavily shape the content. That’s why it’s important to know the reputation of the author before you put credence into what he or she says. In my book, anything Dr. Eric Kandel says is as credible as the most reputable piece of research on the planet.

Case report: now we’re dealing with actual human subjects. However, the problem with a case report is that it tells the story of only one person (n=1). Therefore, it can be unwise to assume that same info will hold true for a group of people.

Case series: in this type of research, several case reports are put together to explain a specific point. A case series takes more than one person into account, but usually less than 20. Since the strength of research is in numbers (i.e., more subjects = stronger argument), you should take a conservative approach when hanging your argument on case studies.

Case-control studies: for this type of study, the medical history of people are compared to the history of people without the disease. The scientists can look at data from the past (retrospective) or assume what might happen in the future (prospective). An example of a case-control study would make a hypothesis such as: there is a relationship between autism and childhood vaccines.

The last three types of research – cohort studies, randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews – hold the most credibility. Collectively, they are known as Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. So whenever you see one of the following three types of research quoted, you can be confident that it’s the most legit science out there.

Cohort study: for this study a group of people are monitored forward in time (prospective) or backward in time to assess the development of disease or some other outcome. An example hypothesis of a cohort study is: adults that exercise for 3 hours/week are less likely to develop diabetes than those who exercise 1 hour/week. Then a specific time period of the data (e.g., 5 years) is examined to determine if the research matches the hypothesis.

Randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT): a group of people are randomly assigned to different treatment groups. This is considered the gold standard in lab research for studying treatments or protocols, especially when there’s a large group of test subjects. A possible RCT hypothesis could be: 15 minutes of high intensity cardio will result in greater fat loss compared to 40 minutes of low intensity cardio.

So the researchers might take 400 people, assign them to either high intensity or low intensity exercise for 12 weeks, then analysis the difference in fat loss between the two groups.

Systematic review: this final type of research is the highest echelon of quality because it’s comprised of the largest amount of available data. A systematic review combines many past studies into one big study. An example hypothesis of a systematic review might be: physical therapy treatment reduces symptoms of low back pain.

If the investigators did their job, they started with a search of all studies about physical therapy and low back pain that meet a pre-set criteria for quality. Then they take the studies that meet the criteria and summarize the cumulative results. Finally, the researchers combine data from all studies and complete a new statistical analysis that’s known as a meta analysis.

If you’re fortunate enough to find a systematic review published in a reputable journal, you can put a lot of faith in the results.

I hope this brief overview of the different types of studies will improve your critical thinking skills and keep you from being bamboozled by research that isn’t reputable.

Stay focused,

CW